A World History of Photography by Naomi Rosenblum.

Don’t be intimidated by Naomi Rosenblum’s 640-page history of photography. It’s surprisingly accessible and unpretentious. It’s a long, but easy, read for anyone who wants to understand photography and photographers in context.

In fact, it’s the context that I appreciate about this work. Rosenblum’s 12 chapters, three short technical histories and five special sections provide insights into the changing styles of photography and photographers over the past century and a half. At the same time, Rosenblum avoids pontification.It seems pretty self-evident that photographs are primarily about seeing. I prefer histories and collections that understand that and help the reader judge a photograph on its own, always visual, terms. That’s the case with Rosenblum’s history.

Don’t misunderstand what I’m trying to say. Photographs can be read in purely visual terms, with no context other than what is presented in the image. But, if that were the only goal of photographic history and criticism, we wouldn’t need histories or critiques.

In my mind, a good writer takes the photograph on its visual terms first, and then layers on that image context which helps the viewer appreciate the image on a richer level. But, too often, writing on photography can take us too far down one of two paths. Either pointing out the obvious to the viewer or reading into the photograph things which the reviewer has concocted regardless of the original intent or vision of the photographer. In either case, it can result in either murdering a good photograph through over analysis or twisting a photographer’s original intentions to meet the prejudices of the writer.

Rosenblum is seldom guilty of this. Instead she has taken great pains to understand both the aesthetic context in which photographs were made and the larger social context at the time.

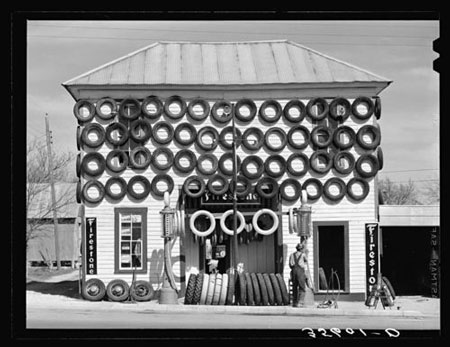

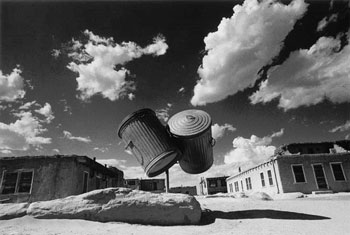

For example, she gently walks the reader through the changing ways in which technology has been viewed by society and the way we have viewed man’s interaction with machine, including Edward Steichen’s celebration of the Flatiron building, Lewis Hine’s crusade against child labor, the Farm Service Administration’s documentation of despair and desolation during the depression, the celebration of technology in images such as Margaret Bourke-White’s documentation of the construction of the Fort Peck Dam and the pure beauty of technology found in the commercial work of Edward Weston, Imogene Cunningham, Charles Sheeler, Steichen and even Hine.

In the end though, a good history of photography should help the reader become a better photographer. By placing images in both social and aesthetic context Rosenblum helps accomplish that.