Perhaps it’s just me. But when I visited three separate exhibitions and a single piece in the Modern Wing of the Art Institute of Chicago they meshed into a larger reflection on the context, connections and cross-pollinating influences of street photography and “New Topographics.”

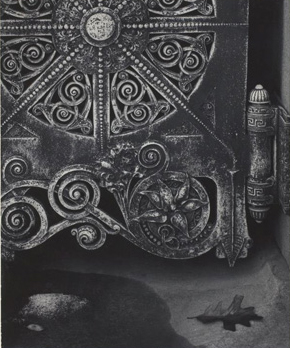

At the center is an exhibit of Lewis Baltz’s Prototypes which were meant to supplement an installation of his Ronde de Nuit (Night Watch) 1991-92. In fact, the Prototypes overshadowed the piece they were meant to complement. Â Ronde de Nuit, is a 35-foot long series which combines images from surveillance cameras and details from the French police station where the cameras were installed. It takes its name from the 1642 Rembrandt painting of the same title.I’m not one to believe that artists shouldn’t be allowed to grow or change over their careers. But, I found Baltz’s Prototypes much more appealing than Ronde de Nuit, which struck me as a bit too much like airport art. That may be more of a complement to airport art directors than an insult to Baltz, since in the nearly 20 years since Ronde de Nuit was first displayed, we have become inundated with commercial works that employ the same disjointed, fragmentary techniques.

I don’t think the work was helped by its installation in a brightly lit hallway of the Institute’s Modern Wing.

At least one description indicates that it was originally exhibited at the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris in a “claustrophobically small passageway.” Looking at the accompanying photo it appears the original installation was in a darkened area recreating the mood of the night that the video cameras survey. Also gone from the Chicago display is the audio recording that apparently accompanied the piece originally.

So, it’s possible the display really didn’t do justice to the original work.

Or, it may just be that the Prototypes are better.

A press release announcing the exhibit declares “Baltz remains substantially concerned over the cancerous spread of our industrially manufactured habitat and how the elements of manufacture can be used to standardize, control, and oppress the inhabitants—ourselves.” The installation itself contains a description that reads in part: “Tension between absorption and resistance – and between image and object – are central to this colossal piece, as they are to Baltz’s earliest photographs, the prototypes…”

My first reaction was: Who writes this crap?

The real gems of the exhibit remain Baltz’s Prototypes, which are known from the landmark “New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape” exhibition at George Eastman House in 1975. The exhibition, considered to be one of the most important of the late 20th century, marked something of a critical point in landscape and “straight” photography, cementing the reputations of not only Baltz but of Robert Adams, Stephen Shore and Bernd and Hilla Becher.

From what I have been able to determine, the Prototypes were not actually part of the New Topographics exhibit, although they are in the same style and date from the same period.

The Bechers’ “Pitheads – Perspective Views, 1981” is part of the permanent collection of the Institute’s Modern Wing. Depictions of industry have a long tradition in photography and photographers have always had a complex relationship with industrial artifacts.

Paul Strand, Edward Weston, Margaret Bourke-White, Charles Sheeler and even Lewis Hine found themselves seduced by the pure beauty of machinery, even as they sometimes railed against the dehumanizing aspects of the industrial age.

I don’t know how the Bechers felt about the industrial artifacts they photographed and it doesn’t seem relevant. The pitheads are simultaneously uniform and unique and it is that contradiction that makes their straightforward presentation so fascinating.  It reminds me a bit of the scolding I receive from my wife when I spot a bird at the feeder and remark it’s “only” a sparrow. For her, there is no such thing as “only” a sparrow, for it might be a chipping, a field, a tree, a song or some other of the innumerable varieties possible.

The Bechers endless cataloguing of industrial artifacts reveals subtle variations and reminds me that someone, or more properly, a group of someones, constructed each of these pitheads as part of a life’s work. How is it, I wonder, that such variety exists in industrial structures all constructed with the same basic purpose in mind?

Certainly the Bechers’ own obsession with cataloging has more than a little in common with the obsessive recording of street life that swallows up many photographers, most notably Garry Winogrand, who left behind 2,500 rolls of undeveloped film and an ex-wife who once said being married to him was like being married to a lens.

I think it’s obvious looking at The New Topographics, that they drew on the influences of candid street photography, which in turn drew on Robert Frank’s intensely personal chronicle of America in the 1950s. So, it was a delight to view Baltz’s Prototypes after seeing two other exhibits at the Institute, a selection of street photography drawn from the Institute’s permanent collection: The Chicago Cabinet and Looking after Louis Sullivan, a collection of architectural photographs by Aaron Siskind, Richard Nickel and John Szarkowski.

The architectural project began as an effort to preserve and catalogue Sullivan’s architecture before it was taken by the wrecking ball. But like Eugene Atget’s images of a disappearing Paris, it clearly and quickly transcended that original purpose.  (An unfortunate footnote is that Nickel, who often sought to salvage details that he was photographing,  was killed on April 13, 1972, while attempting to obtain items for Southern Illinois University – Edwardsville, when a stairwell in the Chicago Stock Exchange building collapsed on him.)

The parallels between Looking after Louis Sullivan and the Bechers are obvious, even if the styles are not. Yet equally direct is the relationship between these photographs and those of Baltz. Viewing  the work of Siskind, Nickel and Szarkowski, and then of Baltz, one sees in the New Topographer’s style a similar, deceptively direct approach that understates the photographer’s compositional decisions. Good composition can be all but invisible. When it is there, it makes an image work. When it isn’t, a picture of a air duct is just a picture of an air duct.

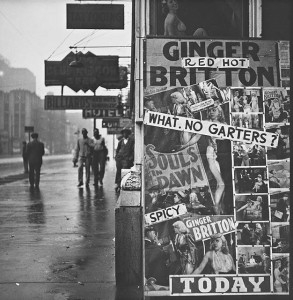

The Chicago Cabinet is a series of exhibits drawing on the collection’s images of Chicago, and the one on display in mid-December 2010 (the second in the series) focused on street photography in Chicago with an emphasis on the streets themselves.

It doesn’t take much to see similarities between David Plowden’s photographs of industrial and agriculture sites in Chicago and Baltz’s Prototypes (unfortunately, I was unable to locate on the web the Plowden images used in the exhibit, so I’ve chosen one that is illustrative, if not identical). However, it would be misleading to make too much of the similarities between one or two photos of Plowden’s included in the Cabinet selection and Baltz. The typical styles of these two very different photographers are far apart. Much of Plowden’s work focuses on preserving disappearing parts of Americana, just as Nickel sought to preserve Sullivan’s work through photography. Baltz focused on contemporary scenes and while the images he produced have their own particular beauty, I doubt if anyone could mistake his photographs for an attempt to preserve the commercial structures he documented.

Walker Evans’ direct head-on style and flair for abstraction (common in some of his best-known works) on the other hand is clearly reflected in the Prototypes. Today, Evans’ photos may evoke feelings of nostalgia, but when he documented the storefronts and interiors of depression-era America, they were as contemporary scenes not as idealized archetypes.

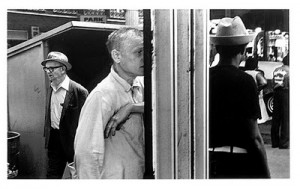

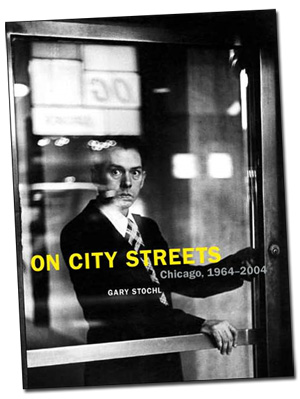

Some of the most interesting street photographs in the Cabinet are those of Gary Stochl. Stochl and Baltz are contemporaries, born just two years apart, but their careers couldn’t have followed more different paths.

By the time he was 30, Baltz’s reputation was already established in the world of art and photography. Stochl worked anonymously until showing up at Columbia College in Chicago in 2004 with a paper bag filled with photos from nearly 40 years shooting the streets of Chicago. Stochl’s job for much of his life was as a caretaker for his parents – apparently the only career that he felt gave him the freedom and time to photograph.

Stochl has generated some controversy within the art world. In a New York Times article from 2005, the director of the Museum of Contemporary Photography at Columbia College Chicago said, “…  if he’s just as good as Robert Frank, or someone like that, we’d rather spend our money on Robert Frank.”

But I think it is unfair to dismiss Stochl as merely a contemporary imitator of Frank. Stochl’s images are visually sophisticated and challenging. Has he been influenced by Frank? Well, who hasn’t? But, Stochl’s vision is clearly his own and he has something unique to say that, while it may draw on Frank’s images, he clearly has his own voice.

The older I become, the more I prefer to judge photographs on the basis of how they look rather than what they purport to say. Stochl’s photographs, like those of Baltz, the Bechers, Siskind, Evans, Nickel, Plowden and the other photographers in these exhibits appeal and challenge the viewer on purely visual terms, which is ultimately, what a photograph is all about.

Pingback: Two Languages: Words and Pictures | Unfocused Blog